A client recently asked this question: "Who actually pays at the 25th percentile?"

Our (perhaps shocking) response: "Well, you do."

**

Many compensation professionals and business leaders have fallen in love with paying above the median.

"We need the best talent possible, so let's pay at the top of the market."

"To be competitive, we have to pay around the 50th or 75th."

"Even ChatGPT tells me my philosophy has to be at the median."

In general, most organizations design their compensation programs to target the market median, or perhaps above the median as cited in the example quotes above. So it wasn't a crazy question for this client to ask: "who actually pays at the 25th percentile?"

The 25th percentile represents a group of people, not a group of companies

In compensation surveys, a reported percentile indicates the salary value at which a certain percent of workers are paid at or below. If the reported 50th percentile (median) is $75,000 that means that 50% of the workers in that group have a salary at or below $75,000. If the 25th percentile for the same role is $60,000, 25% of of the workers in that benchmark are paid at or below $60,000.

This means there are indeed actual workers earning those amounts. It does not reflect what companies are offering for new hires, what a company would like to pay, or an average rate for a company. With few exceptions, it represents the distribution of employee-level pay.

There are two key drivers of the market 25th percentile.

How You Structure Pay:

Organizations target the median, and the range built around it results in 25th percentile pay.

A common approach to compensation management is to build a salary grade structure, with predictable increases in the midpoint of the range and relatively standard width around the midpoints. Jobs are then placed into a grade based on the best fit for the value of the specific job, and pay levels for employees within a role are managed within the aligned range.

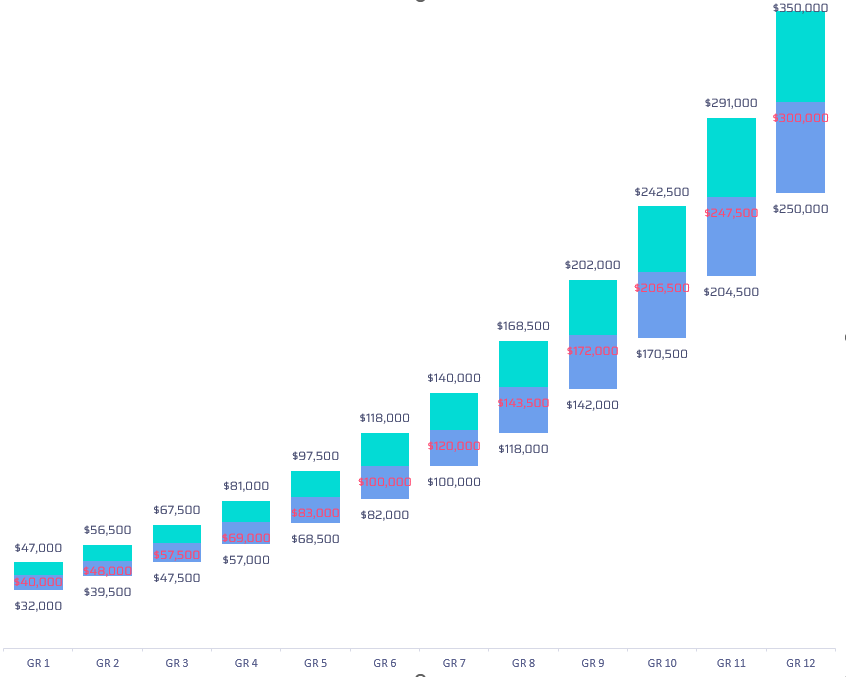

An example structure is shown below:

Assume that we are placing a role into this structure, with the following observed market benchmarks:

| Salary 25th | Salary 50th | Salary 75th |

| $104,500 | $119,000 | $142,000 |

Using the grade structure above, the role is placed into Grade 7, since the Grade 7 midpoint of $120,000 is very close to the market median for the job.

This structure works and aligns with the organizations intent of paying at the median.

But look at the range minimum and compare it to the 25th percentile. Grade 7 has a range of $100,000 - $140,000 - so someone perhaps promoted into that role from a lower grade might be paid at the minimum of the range ($100,000). They are now part of the 25% of workers paid at or below the 25th percentile.

This is not an atypical finding - the 25th percentile of the market is often only 10-15% below the median, which can often mean it falls at or below a defined range minimum.

So who pays at the 25th percentile? Most companies do, at least for some employees. If you build a range around your intended market target, you are likely paying some portion of your workforce lower in the market than your leaders expect.

How You Compete for Talent and Use Talent For Business Success:

Some organizations knowingly - and thoughtfully - offer lower compensation than others.

The illustration and example above make it sound like paying at the 25th percentile is an accident or anomaly. But there are also examples where targeting a below-median market position is a sensible strategy. here are three case examples where a below-median compensaiton strategy has been deployed.

The benchmark reflects a market that's "not really us"

In come cases, available benchmarks aren't fully representative of the talent market. The benchmark may reflect the work, but done in a manner or setting that's not analogous to your organization. For example, a company providing investment research to consumers might still benchmark a stock analyst using the McLagan benchmark for investment management firms, knowing that "buy-side" analysts are ultimately doing different work with very different business economics. It makes sense ot track the market for this role and skill, but it may not be necessary or appropriate to consider those the right talent market.

We simply can't afford to pay at median.

Compensation is a business expense - often a company's largest. If the unit economics of the business require labor at a certain rate to drive profitability, it is a sensible strategy to try attracting and retaining talent at a lower price point. For example, a company providing outsourced lab testing services can only win in the market if it can offer lower cost services than in-house delivery. While achieving scale and increasing productivity can drive down that price point, the organization has also found that it cannot offer rates competitive with what hospital-based labs or R&D facilities are able to pay. It's the same talent market, but different economics that drives the need rate of pay.

We can still attract talent at lower salaries because our value proposition is very different.

It's not always about pay, and certainly not always about base salary. Many organizations choose to have lower fixed compensation in favor of more variable compensation (cash or equity). Other companies focus more on benefits, work life balance, or growth opportunities that decrease the focus on high salaries.

The 25th percentile isn't evil

Market distributions reflect pay in the market, and the 25th percentile simply represents the point below which a quarter of the market is paid. There's nothing inherently good or bad about the 25th percentile - same as the 75th percentile. Ultimately, organizations need to establish a compensation structure that supports their business needs by attracting and retaining the talent needed to drive success. The percentiles... are just math.